Document Type : Original Research Paper

Authors

1 Associate Professor, Department of Urban and Regional Planning and Design, Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism, Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran.

2 M.A. in Architecture, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran.

Abstract

Extended Abstract

Background and Objectives: Low robustness and the loss of appropriateness of spatial development plans facing chaotic and unpredictable conditions emerging from unrecognized uncertainties and unknowns in positivism approaches, has necessitated rethinking about epistemological concepts and fuzzy alternative methods. In the existing legal regulations, the 1200 square kilometers Tehran’s growth boundary, with all the complexities and similarities that it has to a multi-nodal urban area, is considered the same as other cities whose social, economic and political relations are much simpler. To meet this challenge, a broader concept of capital growth area of 6000 square kilometers has been introduced in the planning discourse of this metropolitan area, which has not been realized so far for various reasons, but the preparation of this plan is on the local authority’s agenda. Accordingly, the present study tries to present multiple future narratives and scenarios regarding geopolitical condition, technological progress, divisiveness and managerial and institutional conflict as different types of uncertainties in a new way and with the intention of imaging the plausible futures ahead.

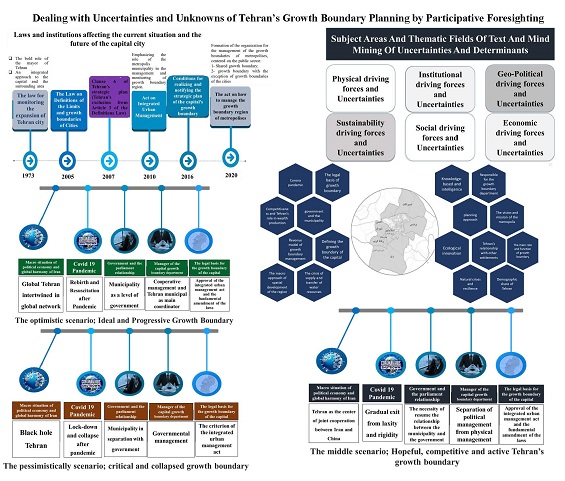

Methods: In order to identify the driving forces affecting the future of the capital’s growth boundary, in-depth interviews were conducted with 13 institutional actors and the main expert from Tehran. Using the structural analysis method or ccross-impact balanced analysis, the drivers identified by the main actors were classified based on two factors: importance and uncertainty. The MicMAC software is utilized to determine the degree of influence and importance, ultimately identifying the most effective variables. In this method, the internal relationships between the elements are explained using a matrix and the opinions of the participants and experiences of different specialists are considered to determine the key variables or, in other words, the key uncertainties. Next, alternative scenarios were determined by the participants in the future workshop and entered into the scenario wizard software. Finally, among them, three scenarios—optimistic, middle, and disaster—were developed.

Findings: One of the most important uncertainties in planning the capital’s growth boundary revolves around institutional and legal factors. These uncertainties encompass various aspects, including the effectiveness of existing laws in addressing boundary issues, the accountability and transparency of trustee institutions, political determination and willingness to establish management structures for the metropolitan area within the boundary, the legal obligations regarding the allocation of financial resources to regional settlements, the official definition of the growth boundary, cooperation and coordination among different organizations, the role and responsibilities of the general department of the growth boundary in managing developments, the provision of necessary financial resources, and the alignment of territorial-functional decision-making procedures. As a result, three scenarios were developed: an optimistic scenario, a pessimistic scenario, and a probable scenario. Paying attention to these scenarios during the decision-making process regarding Tehran’s growth boundary will lead to more resilient and robust plans and strategies.

Conclusion: Finally, to increase the robustness of Tehran’s growth boundary plan against the selected compatible scenario, the following strategic suggestions were presented;

- Creating legal support by redefining the law regarding the definitions of limit zones and growth boundaries. This would involve excluding the metropolitan area of Tehran from the inclusion Notes 1 and 4 of Article 3 of the Law on Definitions of Boundaries and Privacy, aligning it with the executive regulations on definitions of territory and growth boundaries (removing the legal discrepancy from the definition of the capital’s growth boundary);

- Creating an integrated organization for the management of the capital urban growth boundary; coordination and cooperation and participation of all organizations and institutions as integrated management with maximum adherence to the principles of the plan;

- Upgrading the role and position of Tehran Mayor as the executive director of the metropolitan area of Tehran with the supervision of the integrated organization on the realization of the integrated space development plan of the growth boundary;

- Defining common growth boundary region based on the criteria of functional connectedness and the need to manage the growth boundaries of the cities located in the region according to the plan and requirements of the upstream documents;

- Defining a sustainable revenue model by considering and guaranteeing the proportional share and rights of all the cities located in the region;

- Making an agreement on prioritizing issues in the form of a joint document.

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

- Tehran and its urban growth boundary dealing with kinds of uncertainties stemming from geopolitical condition, sanctions, technological progress and institutional conflicts.

- In-depth interview with key actors in Tehran shows 5 critical uncertainties including political economy condition, Iran’s’ global interconnectedness, the alignment of government and municipality, pandemic, city’s trustee and its’ legitimacy.

- Considering 3 main future scenarios and their spatial implications in the process of Tehran’s growth-boundary decision-making and decision-taking will lead to more robust plans and strategies.

Keywords

Main Subjects

این مقاله پژوهشی است که در بخشی از مطالعات مربوط به طرح ساختاری پایتخت به کارفرمایی اداره کل حریم شهرداری تهران و توسط نویسندگان به انجام رسیده است.

This article is derived from a research that was carried out by the authors in a part of the studies related to the structural plan of the capital city, commissioned by the General Department of the boundary of Tehran Municipality.

- Amer, M., Daim, T., & Jetter, A. (2013). A review of scenario planning. Futures, 46, 23-40.

- Ansoff, I. (1957). Strategies for diversification. Harvard Business Review, 35(5), 113-124.

- Benjumea-Arias , M., Castañeda, L., & Valencia-Arias, A. (2016). Structural Analysis of Strategic Variables through MICMAC Use: Case Study. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 7(4), 11-19.

- Bishop, P., Hines, A., & Collins, T. (2007). The current state of scenario development:an overview of techniques. foresight, 9(1), 5-25.

- Brummell, A., & MacGillivray, G. (2016). Introduction to scenarios. Shell International Petroleum Company.

- Brummell, A., & MacGillivray, G. (2016). Introduction to scenarios. Shell International Petroleum Company.

- Centre for Security Studies. (2009). Strategic foresight: anticipation and capacity to act. Zurich: CSS Analyses in Security Policy.

- Conway, M. (2003). An introduction to scenario planning. Foresight Methodologies Workshop. Australia, Victoria: thinking futures.

- Courtney, H., Kirkland, J., & Viguerie, P. (1997). Strategy Under Uncertainty. Harvard Business Review.

- Eames, M., Laurentis, C., Hunt, M., Lannon, S., & Dixon, T. (2014). Cardiff 2050: City Regional Scenarios for Urban Sustainability. Cardiff: Low Carbon Research Institute, Welsh School of Architecture, Cardiff University.technology foresight, forecasting and assessment methods (ص. 47-67). Seville: EU-US Seminar.

- Fernández Güell, J. (2006). Planificación estratégica de ciudades, nuevos instrumentos y procesos. Barcelona: Editorial Reverté.

- Fuerth, L. (2009). Foresight and anticipatory governance. Foresight, 11(4), 14-32.

- Gaub , F. (2019). Global Trends to 2030; CHALLENGES AND CHOICES FOR EUROPE. European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS).

- Godet, M. (2000). Forefront: how to be rigorous with scenario planning. Foresight, 5-9.

- Godet, M., & Roubelat, F. (1996). Creating the future : The use and misuse of scenarios. Long Range Planning, 29, 164-171.

- Habegger, B. (2009). Strategic foresight in public policy: Reviewing the experiences of the UK, Singapore and the Netherlands. Futures, 42(1), 49-58.

- Heijden, K. (2005). Scenarios: The art of strategic conversation. The Wiley Advantage.

- Hines, A., & Bishop, P. (2015). Thinking About the Future: Guidelines for Strategic Foresight. Houston: Hinesight.

- Horton, A. (1999). A simple guide to successful foresight. Foresight, 1(1), 5-9.

- Inayatullah, S. (2011). Future studies: theories and methods. Blanca Manoz: Campo Magnetico Triple.

- Kahn, H., & Wiener, A. (1967). The Year 2000: A Framework for Speculation on the Next Thirty-Three Years. New York: The Macmillan.

- Lennert, M., Robert, J., Aalbu, H., Hallgeir, A., & et al. (2007). Scenarios on the territorial future of Europe. Brussel: ESPON Coordination Unit.

- Markley, O. (1995). The fourth wave: A normative forecast for the future of "SpaceShip Earth.". http://www.inwardboundvisioning.

- Mietzner, D., & Reger, G. (2004). Scenario approaches-History, Differences, Advantages and disadvantages. EU-US Seminar: New

- Miles, I. (2013). Appraisal of Alternative Methods and Procedures for Producing Regional Foresight. European Commission’s DG Research funded STRATA. ETAN Expert Group Action.

- Myers, D., & Kitsuse, A. (2000). Constructing the Future in Planning: A Survey of Theories and Tools. Journal of Planning Education and Research.

- Nedae Tousi, Sahar, 2018, Application of strategic foresight methodology in spatial development planning, The Journal of Architecture and Urban Planning, 20:23-4

- Nedae Tousi, Sahar, 2022, Future research in city and regional spatial development planning, Tehran University Publication

- Peter, K. (2017). The Uncertain Environment. Retrieved April 01, 2017, from FutureScreening: http://futurescreening.com/foresight-framework/the-uncertain-environment/

- Ratcliffe, J. (2002). Scenario Planning: An Evaluation of Practice. University of Salford.

- Ringland, G. (2002). Scenario Planning: Managing for the Future. London: John Wiley & Sons.

- Roy, A. (1981). The Future Field. The Futurist.

- Sardar, Z. (2010). The Namesake: Futures; futures studies; futurology; futuristic;foresight—What’s in a name? Futures, 42, 177-184.

- Schoemaker, P. (1995). Scenario planning: a tool for strategic thinking. Sloan Management Review, 36(2), 25-40.

- Tarh o Rahbord Pouya consulting engineering, 2020, The management plan of the capital sanctuary, General Department of Harim, Tehran.

- Wolfgang Weimer, J. (2013). Constructing consistent scenarios using cross impact balance analysis. ScenarioWizard 4.1. Stuttgart, Germany: Stuttgart Research Center for Interdisciplinary Risk and Innovation Studies.